The Cowichan River, near Stutz Falls. Photo by One Cowichan

(Due to its urgent nature, Mid-Island Focus is printing this release from the Cowichan Watershed Board in its entirety. If you have questions about this report, please contact or subscribe to MiF, and we will look for more answers in a followup story. Craig Spence, Editor)

(Duncan BC) Concerns are rising in the Cowichan Valley as the iconic Cowichan River faces a strong likelihood of running out of water by August unless there is heavy and sustained rainfall. The Cowichan is major salmon producing river, including Chinook which are a critical food source for the endangered Southern Resident orca population. Located on Eastern Vancouver Island, adjacent to the Salish Sea, this river is the heart of the Cowichan Tribes First Nation’s territory, and a favourite recreational destination. It also supports major employment for the region, through fishing, tourism, and the Catalyst Paper mill.

“We’ve been on the knife’s edge several times in the past fifteen years,” says Tom Rutherford, Cowichan Watershed Board Executive Director, “but this is the worst forecast in living memory. Unless we get a lot of rain, there is simply not enough water stored in Cowichan Lake to keep the river flowing to the end of August. Our salmon and the whole ecosystem depend on that water and it’s not there. We are all losing sleep thinking about what lies ahead.”

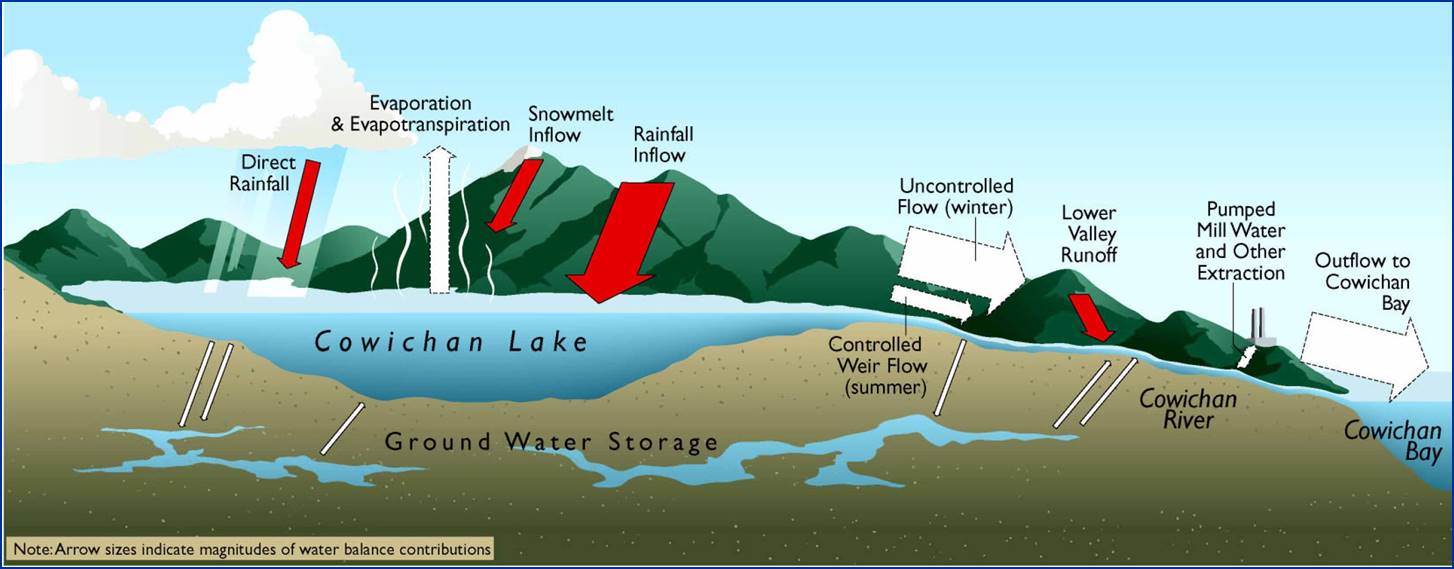

This is primarily a climate change impact. For sixty years, a meter-high, seasonally-operated weir at Cowichan Lake has been used successfully to hold back enough winter and spring run-off to feed the river through the dry summer and fall seasons. A schedule of minimum water flow rates, set by the Province of BC, has been maintained by the water license holder, Catalyst Paper, in return for rights to extract a portion of that water downriver to supply its pulp mill at Crofton. Over the past fifteen years, however, much drier spring and summer weather combined with lower snowpack has left insufficient water supplies in Cowichan Lake to meet those minimal flows in most years. This impacts fish survival, First Nations constitutional rights, recreation, tourism, the 600 workers of PPWC Local 2 at the Catalyst mill, and more.

This year an emergency measure is in place allowing Catalyst to pump water out of the lake into the river when the lake storage is depleted, but this is an expensive stop-gap response. While it could help keep the river flowing at minimal levels, it would result in drawing down the lake below historic levels. This could impact other fish, riparian habitats, and lakeshore residents, and is only viable as a short term remedy. Often the fall rains don’t return until October.

“It’s all hands on deck,” says Rutherford. “Local organizations are doing everything we can here.” A partnership of Cowichan Valley Regional District, Cowichan Tribes, Catalyst Paper and the Cowichan Watershed Board were recently invited to apply for major funding to begin the next phase to replace the weir. If successful, engineering and impact analysis will begin this year to build a structure capable of storing more water.

More info at cowichanwatershedboard.ca